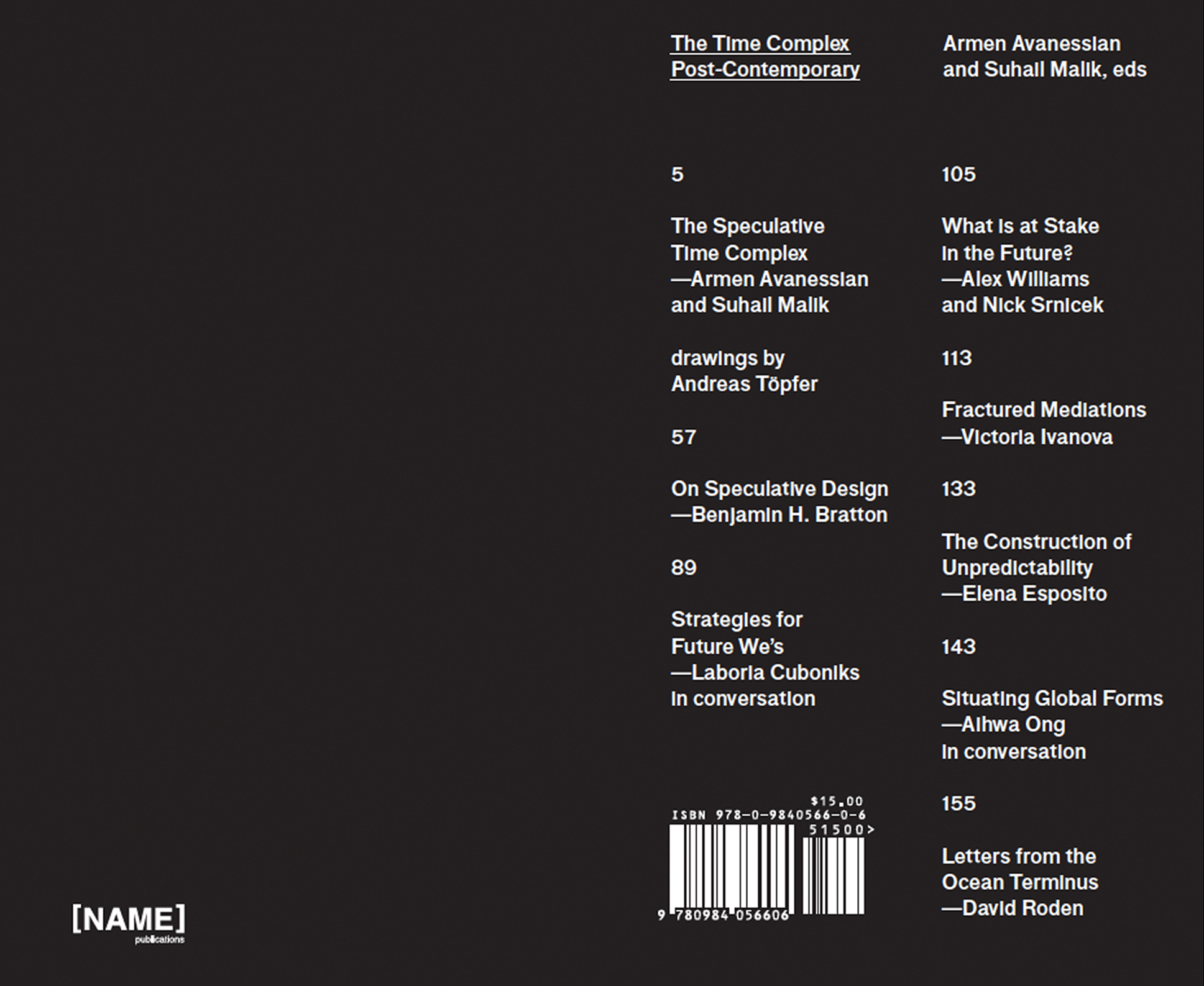

These exerpts are taken from a written discussion between Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik. They discuss the bewildering notion of the post-contemporary condition, which is distinctly connected to theories of time complex. These quotes have proved invaluable to the concluding section of my dissertation.

Time Complex – Post-contemporary – Avanessian, Malik, 2016 P: 7 -56

Avanessian: The basic thesis of the post-contemporary is that time is changing. We are not just living in a new time or accelerated time, but time itself – the direction of time – has changed. We no longer have linear time, in the sense of the past being followed by the present and then the future. It’s rather the other way around: the future happens before the present, time arrives from the future. If people have the impression that time is out of joint, or that time doesn’t make sense anymore, or it isn’t as it used to be, then the reason is, I think, that they have – or we all have – problems getting used to living in such a speculative time, or within a speculative temporality.

Malik: The main reason for the speculative reorganization of time is the complexity and scale of social organisation today. If the leading conditions of complex societies are systems, infrastructures and networks rather than individual human agents, human experience loses its primacy, as do the semantics and politics based on it. Correspondingly, the present as the primary category of human experience - in its biological sentience at least – which has been the basis for both the understanding of time and of what time is, also loses its priority in favor of what we could call a time-complex. It is no longer necessary to explain the movement of the past and the future on the basis of the present. We are instead in a situation where human experience is only a part of – or even subordinate to – more complex formations constructed historically and with a view to what can be obtained in the future. The past and the future are equally important in the organization of the system and this overshadows the present as the leading configuration of time. Complex societies, which means more than human societies at scales of socio-technical organisation that surpasses phenomenological determination, are those in which the past, the present and the future enter into an economy where maybe none of these modes is primary, or where the future replaces the present as the lead structuring aspect of time.

Avanessian: What happens in the present is based on a pre-emption of the future, and of course this is also linked to what has been called a tendency towards premeditation in the media.

Malik: Everything now seems to be ‘post’ – something else, which indexes that our understanding of what is happening now has some relation to but is also disconnected to historically given conditions. While the ‘pre’ indexes a kind of anticipatory deduction of the future that is acting in the present - so that the future is already working within the now, again indicating how the present isn’t the primary category but is understood to be organised by the future – what the ‘post’ marks is how what’s happening now is in relation to what has happened but is no longer. We are the future of something else. The ‘post-’ is also a mark of the de-prioritization of the present.

If we are post-contemporary, or post-postmodern, post-internet, or post whatever – if we are post-everything – it is because historically-given semantics don’t quite work anymore. So in a way, the present itself is a speculative relationship to a past that we have already exceeded. If the speculative is a name for the relationship to the future, the ‘post’ is a way in which we recognise the present itself to be speculative in relationship to the past. We are in a future that has surpassed the conditions and terms of the past.

Combined, the present is not just the realization of the speculative future (the pre), but also a future of the past that we already exceeding. We don’t quite have the bearings or the stability or the conventions that the past offers to us (the post).

Avanessian: The shaping of the present is not necessarily determined by the past. The present can no longer primarily be deduced from the past nor is it an act of pure decisionism, but its shaped by the future. That’s the key problem and key indication that the logic of the contemporary with its fixation on the present – the human fixation on experience – that this presentism has difficulties or even completely fails in dealing with the logic of being constituted by the future. That’s partly the reason for all the critical reasoning and questioning of contemporaneity in recent years that happened parallel to the so-called speculative turn.

Speculative realism has mostly argued for an intra-philosophical or conception notion of speculation, which is to think of the outside of though and the experience of thought. The interest of the post-contemporary is to understand and operationalize the present from outside of itself.

Malik: The future is acting now to transform the present even before the present has happened. It is not only the linear schematic of time that is scrambled but also the very openness of the present to the future.

Avanessian: The tense system is really important to our understand and construction of time, it structures our experience. ‘Every past was a future’ and ‘every future was a past’ – these basic structural paradoxes can be tackled via an analysis of grammar.

Malik: The identification of the speculative time-complex we are here calling the post-contemporary is that they articulate a time structuring in which the present drops out. So determinations of time can be established that don’t require the present as their basis.

What we have with the speculative time-complex is that the future, which includes the future we don’t know, gets included within the current reckoning, and the present is becoming disconnected from the past. The dismantling of the linear ordering and the primacy of the present equalizes the past, present and future.

Avanessian: The present is not fully experiencable but is split in itself. The tense structures can actively operationalise this splitting. It is laden with innumerable past-presents. It presents actual phenomena as post-X phenomena and it desynchronizes time.

Malik: The future itself becomes part of the present. This could be taken as an extension of the present without a future radically distinct from it. And it often is, with the leftist-critical claim of the loss of futurity under the capitalism of complex societies. (Link to Jameson’s theories)

Avanessian: With left-critical reactions, there is a kind of suffocation, to the extent that most people have the feeling of not being able to gain traction in the present, to change something, and to have something like a future worthy of its name.

Malik: What the right does is to simplify the time-complex, reduce it and re-centre it on the present as the dominant moment on the basis of tradition. The right has always done this in modernity: if modernity is a paradigm in which the new happens in the now, what has characterized the right is a defense against the emergence of the new as the basis for actions, social organizations, aesthetics, meaning and so on. The authority of past conditions is invoked as a stabilization mechanism for modernization. The right is not necessarily against modernization but stabilizes its disruptive effects by calling on what are then necessarily conservative or reactive historical formations. And faced with operationalised speculative time-complex of neo-capitalism, the right can in a way carry on doing what is has always done without necessarily reorganizing that what it is reacting against is no longer the modern but a new condition.

In a way, leftism makes the problem of the contemporary more evident because the left in its progressive forms has been attached to modernism. Instead of seeing the future as the condition of the present, the present is instead taken to extend out indefinitely and cancel out the radically different future.

The speculative present as we are identifying it is, by contrast to this leftist melancholy, the entrenchment of the future and the past which folds into the present, in a way that certainly de-prioritizes it and maybe even makes it drop out. The past was the future, and the future will be the past.

There us no critical interruption from the present in this speculative present. It is constructed by the uncertainties of the future and the absence of the past. That’s why the left-critical thinking of the event or the emptiness or openness of the present – of contemporaneity – is still vestigially modern. It’s not adequate to the tasks and conditions of the twenty-first century.

Avanessian: What the left sees in the speculative complexification of time is an extension of the present that than its thinning out by the forcing of the future or the disestablishment of the past. Historical, futural, anticipatory relationships are maintained with an emphatic insistence on the presentness of action, aesthetics or experience. The 'contemporary' is a time form that saturates both the past and the future, a meta-stable condition.

A leftism still attached to Modernism won’t have traction on the speculative present, even if the leftism is more attentive to the time-complex than the right because it is not trying to restore the past. Even it its accepted that the left is more open to modernity than the right, it holds that the present extends into both the past and into the future, which supposedly destroys the future as a future.

Malik: The present now is not the time in which the decisions are made or the basis for the new, as it was in Modernism. The new is happening instead in a transition between the past and a future that is not a unidirectional flux, but a speculative construction in or from the directions of past and present at once.

Under the guise of the contemporary, the modernist left has a kind of melancholia for a future that it cancels to preserve its received premise: the present. The past and the future are taken as modifications of the present. The advantage for left-criticality is that the contemporary can then accommodate, dissimilate, colonize all of time in its own terms.

Avanessian: Contemporary critical art mostly produces different – essentially decorative – objects or meanings that maintain the reduced form of the speculative time complex. The post-contemporary works within the speculative present, it understands it, it practices it, and it shapes our temporality.

Malik: The future is only just a set of potentials that must never be actualized for fear of instrumentalization and, paradoxically and self-destructively, realizing in any present a future radically distinct from the present.

We have to open up the time-complex in its infrastructures that are more structured in terms other than those of human languages. Even more generally, we need a grammar adequate to the expansive infrastructure of the time-complex in its widest formation.